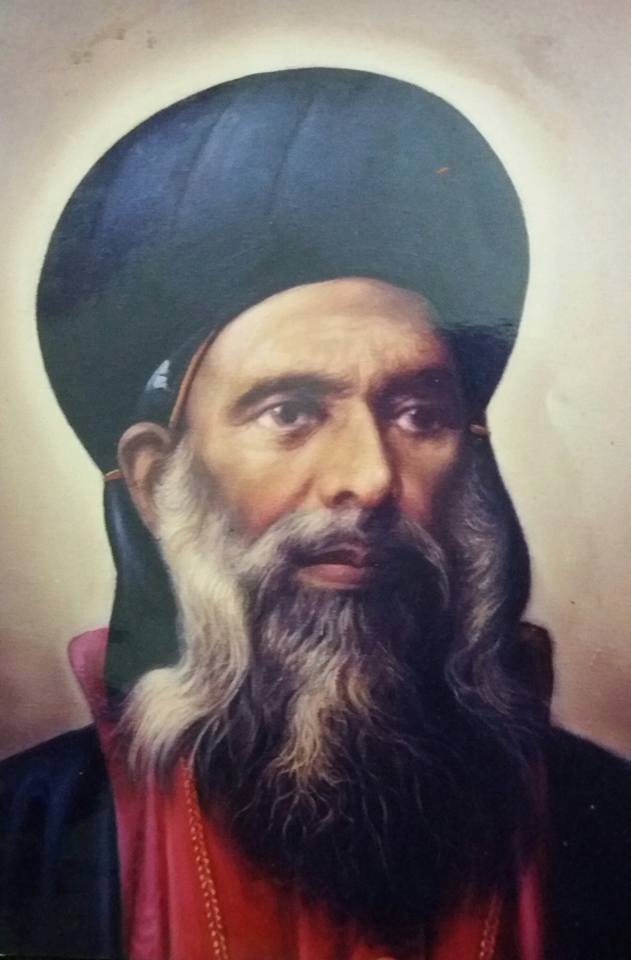

Poet, teacher, orator and defender of the faith, and known by the Syrian Orthodox church as Doctor of the Holy Church declared as the Doctor of the universal Holy Church. Also in 1920 Pope Benedict XV; declared him the doctor of the church.

Ephrem Born c. 303/6 in Nisibis (Today Nusaybin, Turkey), Mesopotamia; died at Edessa (Urfa, Turkey) on June 9, 373; Most historians infer from the lines quoted above that Ephrem was born into a Christian family -- although not baptized until an adult age (eighteen old) at St. Mary in Amid-Diyarbakir,Turkey, (the trial or furnace), which was common at the time. Ephrem passed his entire life in his native Mesopotamia (Syria) possibly in Nisibis where he spent most of his adult life.

From the time of his childhood Ephrem was known for his quick temper and irascible character, and in his youth he often had fights, he acted thoughtlessly, and even doubted of God's Providence, until he finally recovered his senses from the Lord's doing, guiding him on the path of repentance and salvation. One time he was unjustly accused of the theft of a sheep and was thrown into prison. And there in a dream he heard a voice, calling him to repentance and rectifying his life. After this, he was acquitted of the charges and set free.

Within Ephrem there took place a deep repentance. He came was served under Saint James bishop of Nisibis. Among the hermits especially prominent was the noted ascetic, a preacher of Christianity and denouncer of the Arians, the bishop of the Nisibis Church, Saint James (Comm. 12 May). The Monk Ephrem became one of his disciples. Under the graced guidance of the holy hierarch, the Monk Ephrem attained to Christian meekness, humility, submission to the Will of God, and the strength without murmur to undergo various temptations. Saint James knew the high qualities of his student and he used them for the good of the Nisibis Church -- he entrusted him to read sermons, to instruct children in the school, and he took Ephrem along with him to the First Ecumenical Council at Nicea (in the year 325). The Monk Ephrem was in obedience to Saint James until the bishop's death in 338.

Thenceforth he became more intimate with the holy bishop of Nisibis, who availed himself of the services of Ephrem to renew the moral life of the citizens of Nisibis, especially during the sieges of 338, 346, and 350. One of his biographers relates that on a certain occasion he cursed from the city walls the Persian hosts, whereupon a cloud of flies and mosquitoes settled on the army of Sapor II and compelled it to withdraw. The adventurous campaign of Julian the Apostate, which for a time menaced Persia, ended, as is well known, in disaster, and his successor, Jovianus, was only too happy to rescue from annihilation some remnant of the great army which his predecessor had led across the Euphrates. To accomplish even so much the emperor had to sign a disadvantageous treaty, by the terms of which Rome lost the Eastern provinces conquered at the end of the third century; among the cities retroceded to Persia was Nisibis (363). To escape the cruel persecution that was then raging in Persia, most of the Christian population abandoned Nisibis. Ephrem went with his people, and settled first at Beth-Garbaya, then at Amid, finally at Edessa, the capital of Osrhoene, the site of a famous theological school, was where he did most of his writing, and where he spent the remaining ten years of his life, a hermit remarkable for his severe asceticism. St. Ephrem did not live in easy times in Nisibis.

Several ancient writers say that he was a deacon; as such he could well have been authorized to preach in public. At this time some ten heretical sects were active in Edessa; Ephrem contended vigorously with all of them, notably with the disciples of the illustrious philosopher Bardesanes. To this period belongs nearly all his literary work; apart from some poems composed at Nisibis, the rest of his writings-sermons, hymns, exegetical treatises-date from his sojourn at Edessa. It is not improbable that he is one of the chief founders of the theological "School of the Persians", so called because its first students and original masters were Persian Christian refugees of 363.

Tradition tells us that during the famine that hit Edessa in 372, Ephrem was horrified to learn that some citizens were hoarding food. When he confronted them, he received the age-old excuse that they couldn't find a fair way or honest person to distribute the food. Ephrem immediately volunteered himself and it is a sign of how respected he was that no one was able to argue with this choice. He and his helpers worked diligently to get food to the needy in the city and the surrounding area.

The famine ended in a year of abundant harvest the following year and Ephrem died shortly thereafter, as we are told, at an advanced age. St. Ephrem passed away on June 9, 373 as accepted by many. Ephrem relates in his dying testament a childhood vision of his life that he gloriously fulfilled:

"There grew a vine-shoot on my tongue: and increased and reached unto heaven, And it yielded fruit without measure: leaves likewise without number. It spread, it stretched wide, it bore fruit: all creation drew near, And the more they were that gathered: the more its clusters abounded. These clusters were the Homilies; and these leaves the Hymns. God was the giver of them: glory to Him for His grace! For He gave to me of His good pleasure: from the storehouse of His treasures."

At his death St. Ephrem was borne without pomp to the cemetery "of the foreigners". The Armenian monks of the monastery of St. Sergius at Edessa claim to possess his body.

The life of St. Ephrem, it is certain, however, that while he lived he was very influential among the Syrian Christians of Edessa, and that his memory was revered by all, Syrian Orthodox, and Nestorians. They call him the "sun of the Syrians," the "column of the Church", the "harp of the Holy Spirit". More extraordinary still is the homage paid by the Greeks who rarely mention Syrian writers. Among the works of St. Gregory of Nyssa (P.G., XLVI, 819) is a sermon (though not acknowledged by some) which is a real panegyric of St. Ephrem.

St. Ephrem the Syrian, left us in Syriac hundreds of hymns and poems on the faith that inflamed and inspired the whole Church, and became so famous that his writings are publicly read in some churches after the Sacred Scriptures. Sozomen pretends that St. Ephrem wrote 3,000,000 verses, and gives the names of some of his disciples, some of whom remained orthodox, while others fell into heresy (Hist. Eccl., III, xvi). From the Syrian and Byzantine Churches the fame of Ephrem spread among all Christians. The Roman Martyrology mentions him on February 1. In their menologies and synaxaria Greeks and Russians, Chaldeans, Copts, and Armenians honor the holy deacon of Edessa.

"I have chanced upon weeds, my brothers, That wear the color of wheat, To choke the good seed."

According to tradition, Ephrem began to write hymns in order to counteract the heresies that were rampant at that time. For those who think of hymns simply as the song at the end of Mass that keeps us from leaving the church early, it may come as a surprise that Ephrem and others recognized and developed the power of music to get their points across. Tradition tells us that Ephrem heard the heretical ideas put into song first and in order to counteract them made up his own hymns. In the one below, his target is a heretic Bardesan who denied the truth of the Resurrection:

"How he blasphemes justice, And grace her fellow-worker. For if the body was not raised, This is a great insult against grace, To say grace created the body for decay; And this is slander against justice, to say justice sends the body to destruction."

The originality, imagery, and skill of his hymns captured the hearts of the Christians so well, that Ephrem is given credit for awakening the Church to the important of music and poetry in spreading and fortifying the faith.

Many Churches still find singing in church a problem, probably because of the rather individualistic piety that they inherited. Yet singing has been a tradition of both the Old and the New Testament. It is an excellent way of expressing and creating a community spirit of unity as well as joy. St. Ephrem's hymns, an ancient historian testifies, "lent luster to the Christian assemblies." We need some modern Ephrems—and cooperating singers—to do the same for our Christian assemblies in Diaspora today.

REFERENCES