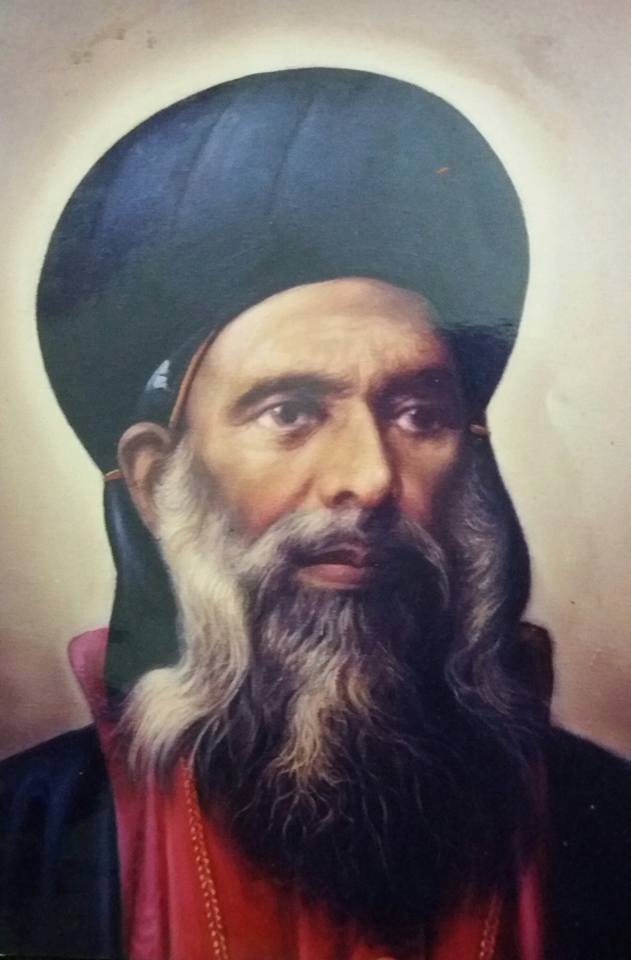

St. Jacob Baradaeus (James or Jacob) was born at Tella Mouzalat, near Nisbis, which is 55 miles East of Edessa. Tella Mouzalat is also referred in certain texts as Constantina. He was born as the son of Theophilus (Theophilus Bar-Manu) who was a priest of the Syrian Orthodox Church (Smith & Wace, 1882; Patriarch Aphrem I, 2000). His parents were not having children for a long time and in pursuance of a vow of his parents he was dedicated to God. At the age of 2 years, Jacob was entrusted to the care of Eustathius, the chief of the Monastery (Reesh Dayro), at Phaselita, near Nisbis (Paulose Aphrem, 1963). He learnt Greek, Syriac and the basics of asceticism at the monastery.

One day Jacob’s mother visited the monastery and wanted to take him with her. He was not willing to go home even for a visit and said: “I am fully dedicated to Christ and that my mother has no share in me.” After this incidence, his mother died in about a year and his father died in about three years (Paulose Aphrem, 1963). After the death of his parents he distributed all the properties that he inherited from his parents among poor people and reserved nothing for himself (Smith & Wace, 1882). He said: “Let the wealth of the world be to the world.” He released two slaves whom he inherited and left the house and estate for them.

After the training at Phaselita monastery, Jacob was ordained deacon and subsequently became a priest. Jacob was reputed for working miracles, and sick people came from far and near to be healed by him. St. Jacob raised the dead, the blind were restored to sight, rain was given, and even the Sun was made to stand still. Edessa, when attacked by Chosroes I, after the capture of Batnae (Isnik in Turkey, the place where Council of Nicea met in A. D. 325; Fuller, 1655), and other towns on the Euphrates, the prayers of St. James (Jacob) saved the people and Chosroes was scared by a terrific vision (Smith & Wace, 1882). His fame spread over the East. The empress Theodora, a zealous partisan of Jacobites (Syrian Orthodox Christians were called Jacobites after the leadership of St. Jacob-Jacob) wanted to see him. However, Jacob was not inclined to go to Constantinople. Later, in a vision, Severus, the Patriarch of Antioch, and Mor John, the late bishop of Tella, directed him to go to Constantinople to which he obliged. He went to Constantinople in about A. D. 528 and remained there in a monastery for fifteen years (Cross & Livingstone, 1974).

On the arrival of St. Jacob at Constantinople, Theodora received him with honour, but the court had no concern for him. Justinian, the emperor, had resolved to enforce the Chalcedonian decrees universally, and the bishops and clergy who refused to accept the decrees were punished with imprisonment, deprivation, and exile. As a result, Jacobites were deprived of their spiritual pastors and for about ten years many churches had been destitute of the sacraments. The faithful were not ready to accept sacraments from the heretics. Since the emperor ardently supported Chalcedonians, they were known as the Melchites (Malchoye- the royal party or the Emperor’s men).

Al-Harith (Aretas) ibn Jabalah al-Ghassani, the Sheik of the Christian Arabs (A. D. 530-572), appealed to Theodora, and Jacob was given a little freedom. At that time, a number of bishops from all parts of the East, including Theodosius of Alexandria, Anthimus, the deposed Patriarch of Constantinople, Constantius of Laodicea, John of Egypt, Peter and others came to Constantinople to mitigate the displeasure of the emperor. But they were detained in a castle in a kind of honourable imprisonment. They ordained Jacob as the bishop of Edessa in c. A. D. 541 (the date given by Asseman). Some authors have given the date as 542 or 543 (Cross & Livingstone, 1974; Patriarch Aphrem I, 2000).

The Syrian Orthodox Church should gratefully remember Jacob Baradaeus for he is responsible for restoring the Church from extinction by his indomitable zeal and untiring activity. The Church was threatened by the persecution of the imperial power. The Christological doctrine (two natures in Christ) set forth by the Chalcedon synod (451) was not acceptable to the Syrian Orthodox Church. The political and dynastic storms although swept that portion of the world, efforts of St. Jacob preserved the Church whereby the Church since 6th century is known as the Jacobite Church.

Jacob Baradaeus travelled on foot the whole of Asia Minor, Syria and Mesopotamia, and adjacent provinces, even to the borders of Persia. He both exhorted the faithful and sent encyclicals encouraging them to maintain the true faith. He ordained 89 (27?) bishops and two Patriarchs (Smith & Wace, 1882). The Patriarchs probably are Sergius (544-547) and Paul II (550-578). Paulose Aphrem (1963) has recorded that in A.D. 550 St. Jacob (James) with the help of Augen, the Episcopa of Selucia, ordained Paul of Egypt as Patriarch of Antioch. Justinian, the emperor, and Catholic bishops were angry at the successful missionary labour of St. Jacob. Orders were issued for his apprehension and rewards were offered for his capture. However, in his beggar’s garb, aided by the friendliness of Arab tribes and other chiefs and the people of Syria and Asia, he eluded all attempt to seize him. His labours paved the way for establishment of the Church as the National Church of Syria (Cross & Living stone, 1974). Imperial persecution could not repress his work. Although there were many converts to Islam after the Arab invasion of Syria (c. 640), the Jacobite Church continued to produce a number of writers.

Jacob Baradaeus is known by the surname Baradaeus. The surname Baradaeus is derived from ‘baradai’ (clad in rags) or the ragged mendicant’s garb, patched-up out of the old saddle-cloths which he used for his swift and secret journeys in Syria and Mesopotamia to avoid arrest by the imperial forces (Smith & Wace, 1882; Douglas, 1978). John of Ephesus states that the origin of his surname is that he cut a coarse robe into two pieces, and wore one-half as an under garment, and the other half as an upper garment without changing them during summer or winter until they grew quite ragged and tattered. Burd’ono, the nickname is derived from the Syriac word “Burd- o” meaning saddle-cloth. The origin of the word from Arabic, Greek and Latin equivalents are detailed in Smith & Wace (1882, P. 329).

In the 5th and 6th centuries a large body of Christians in Syria repudiated those who had supported the Council of Chalcedon (451) in affirming the dual nature of Christ. The Christological teaching of the Chalcedon can be summarized as: “we confess one and the same Christ Jesus, the Only-begotten Son, whom we acknowledge to have two natures, without confusion, transformation, division or separation between them. The difference between these two natures is not suppressed by their union; on the contrary, the attributes of each nature are safeguarded and subsist in one person” (Poulet, 1956, pp. 240-241). Some writers refer to the Syrian Orthodox faith as monophysitism which is totally wrong. Monophysitism is a Christological teaching of Euthyches that human nature of Christ was absorbed by the divine (Encyclopedia Americana, 1988). The Christological differences are now understood to be the problem of use of vocabulary rather than ideological.

Like many Copts, Ethiopians, and Armenians, Syrian Orthodox Church hold that Christ is not “in two natures” (human and divine) but is “one nature out of two natures.” St. Severios, the Patriarch of Antioch (A. D. 459-538), taught that “… all the human qualities remained in Christ unchanged in their nature and essence, but that they were amalgamated with the totality of hypostasis; that they had no longer separate existence, and having no longer any kind of centre or focus of their own, no longer constituted a distinct monad. On the contrary, the foci had become one. The monads were conjoined; the substratum in which the qualities of both natures inhered no longer had an independent subsistence, but formed a synthesis, and all the attributes subsisted in this composite hypostasis” (Smith & Wace, 1887, Vol. IV, p. 641).

Jacob Baradaeus, bishop of Edessa, was instrumental in organizing their community; hence, they have been termed Jacobites" (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2001). There were trustworthy bishops who supported Jacob Baradaeus. They include Mor John of Asia, Mor Ahudeme’ (the Persian King Kizra Anusharvan martyred him in A. D. 575) and Mor Yulian. John of Asia, a contemporary of Jacob Baradaeus, has written two biographies about him. They are: Anecdota Syriaca, Vol. II, edited by J. P. N. Land in 1875 (pp. 249-253; pp. 364-383) and Ecclesiastical history Part III, Payne Smith’s translation (pp. 273-278, 291). Bar Hebraeus account of Jacob Burdono written in 13th century in the Chronicon Ecclesiasticum relies on the above mentioned books (Cited in, Smith & Wace, 1882).

Jacob Baradaeus died at the monastery of Romanus or Cassianus on July 30, 578 (Douglas, 1978; Patriarch Aphrem, 2000). His episcopate is said to have extended over 37 years, and his life, according to Renaudot to 73 years. According to a short account by Cyriacus, bishop of Mardin, the remains of Jacob Baradaeus were kept at the monastery of Cassian until A. D. 622 (621?). Thereafter the relics were translated to his monastery of Phaselita, near Tella Mouzalat by Mor Zakkai, the episcopa of Tella (Paulose Aphrem, 1963). He has written a liturgy in fifteen pages beginning with “O Lord, the most holy Father of peace” and several letters, which are published in Syriac. The feast of Mor Jacob Baradaeus, the protector of faith, is celebrated on November 28.